09:00 Incredible though it may sound, Lois and I spend almost the morning on the NHS website trying to get her the facility to order repeat prescriptions online. These efforts include failed attempts to upload pictures of her holding up her driving licence, pictures of her driving license without her holding it up, and a video of her saying 4 chosen digits selected by the website. I won't say it's madness, because you already know that!

The website is really poor, in my opinion, and we wonder how people less sophisticated than us get on - assuming, of course, that there are such people!

In the end we think we succeed in getting Lois this facility, but only after we ring our local doctor's surgery to get some information demanded by the website. So, in the end, it seems like a success, let's wait and see, shall we, before we congratulate ourselves. If we ring up the pharmacy on Monday and they say they've got the medication ready for us, then we'll relax, but until then the jury's still out!

14:00 I'm a member of Lynda's U3A "Making of English" group, which is holding its monthly meeting tomorrow afternoon on zoom, to talk about the proposition that "Americans Speak Elizabethan English".

It's a pity, but I've had zero time this week to do any reading in preparation for this meeting, so this afternoon I read John Hurt Fisher's essay on "British and American continuity and divergence", which turns out to be very interesting, and from which I learn a number of interesting facts that I didn't know before.

It seems to me that it's normally quite hard to tell reliably from a piece of writing whether the writer is British or American - sometimes you can, but most often you can't. The differences in written English are not that significant in my view. But on the other hand, as soon as somebody opens their mouth, one can pretty reliably distinguish the two, with very few exceptions. It's the pronunciation that's the main divider, isn't it, but it doesn't normally affect mutual comprehensibility, which is a relief!

But who knew this interesting fact mentioned by Fisher, that, way back in the "impressment controversies" between the two countries in the 1790's, naval captains on both sides were finding it so difficult to decide whether a sailor was British or American, that the US Government even proposed issuing certificates of citizenship!

According to Fisher, until the later decades of the 18th century, in both countries, almost everybody in the US and UK spoke with some sort of local accent, the only exception being the numerically insignificant gentry.

However, a big change was coming on this side of the Atlantic. Beginning in the 1770's or thereabouts, a change started in England, leading to the development of RP (Received Pronunciation), the posh kind of English used for decades by the BBC. At that time RP speakers still represented only a tiny proportion of the population, but they were the most influential group, and heavily associated with the circles of power in the London area.

After American independence in the 1780's, there followed a period when US travellers rarely visited Britain, but eventually this changed, and when it did and the Americans started visiting Britain again, they were said to have been astonished at the changes in the language that they heard in socially elevated circles in London, representing the early phases of RP.

How different are the two pronunciations today?

Well, Fisher comments that a big difference is that American English is predominantly rhotic, whereas UK English these days is predominantly non-rhotic - non-rhotic means that the letter 'r' is not pronounced in a word if it comes after a vowel, unless the 'r' itself is followed by another vowel. With rhotic speech the letter 'r' is normally always pronounced.

the shrinking areas of rhotic speech in England

But who knew that in England before 1700, non-rhotic speech, now regarded as the standard here, was looked on as really vulgar, and was mainly confined to words where 'r' is followed by 's'? Hence if you were really uneducated, you might pronounce words like "horse" as "hoss", and "curse" as "cuss", a pronunciation which is really old - it started to be heard around 1300, You still hear it occasionally today of course, although it's still non-standard, and regarded as a bit crude still.

Fisher also has some other interesting observations on non-linguistic factors. He remarks that the earliest immigrants to the US from the British Isles were, socially, by no means from the bottom rung of the ladder, and were usually of at least artisan (skilled worker) level or above, and they had usually had a reasonable education. These were the people with the vision to see the possibilities of a better life across the Atlantic, and the means of securing a passage. Uneducated agricultural workers were almost entirely absent from the ships carrying early immigrants. This changed later, when dispossessed and discontented immigrants from Scotland, Ireland and Northern England arrived in the US later on in the 19th century, when passages by ship became more affordable.

Fascinating stuff isn't it! I'll have to try and read some more of it tomorrow morning if I can.

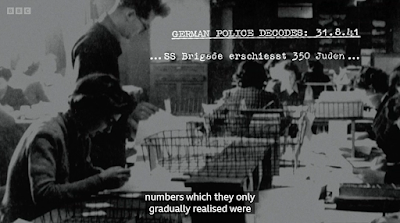

20:00 We steel ourselves and decide to watch the rest of programme two in Ken Burns mammoth 3-part documentary series "The US and the Holocaust".

No comments:

Post a Comment